The Magic Of Iyengar Yoga

We may begin attending Iyengar yoga classes because of their physical benefits, but the reason so many of us stay is that there is an inkling that some other sort of magic is at play. What is that magic? What is it that makes Iyengar yoga so rich, transformative and profound?

Iyengar yoga is implicitly connected with yoga philosophy. A basic understanding of yoga philosophy is necessary for any serious student of Iyengar yoga. Every classical Indian philosophical school, of which yoga is one, has a source text upon which its system is based. The root text on yoga is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. It is the authoritative text that explains yoga's framework and what yoga is. Patanjali, within a compilation of nearly 200 sutras, lays out an 8 limbed path (astanga yoga) that needs to be followed to reach success in yoga. These eight components are yama (social ethics), niyama (personal ethics), asana (posture), pranayama (breathwork), pratyahara (sense control), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (yoga). Whereas it is usual for asana to be one limb in itself, and traditionally taken to prepare the body for the higher limbs which require the body to sit for long periods of time in a meditative state, Iyengar yoga attempts to incorporate all eight limbs within the one limb of asana itself.

In Iyengar yoga much emphasis is placed on the alignment and precision of the pose. One is attempting to cultivate the intelligence of the body in order to create a correct extension and asana presentation. This means an even extension where there is no under stretch or overstretch and no unnatural distortion of the body. BKS Iyengar says ‘asanas are not contortions, but the art of positioning the body in different shapes without altering its anatomical structure.’ Moreover, when a pose is done correctly so that it is being held through the bone structure, as opposed to being held muscularly, there is a steadiness due to its firm foundation, and there is a sense of comfort (within the discomfort) due to the load of the pose being taken evenly throughout the body. Let us see how this is connected with yoga philosophy and Patanjali's eight limb path.

The Foundation: The Yamas & Niyamas

There are five components to the first limb in Patanjali’s eight-step path, yama, or social ethics. They are ahimsa (non-violence), satya (speaking the truth), brahmacharya (conserving energy), asteya (non-stealing), and aparigraha (non-coveting). When generating a correct extension in asana one is avoiding the violence of overstretching. Conversely, when under stretching unconscious violence is being created because the cells of that part eventually wither and die as they are not being made to perform to their optimum function. One is in satya, or truth, when a correct asana is being executed because the reality of our embodied being is being directly experienced. Practise of this kind requires total attention, and thus leads to brahmacharya, or energy conservation, as the wayward mind is drawn inwards and is coaxed away from the energy-depleting activity of being driven by various wants and desires. A correct asana also develops a sense of inner contentment which liberates one from greed or the need to obtain things from elsewhere. In this way, both the principles of asteya (non-stealing) and aparigraha (non-coveting) are integrated into the practice of asana.

Just as there are five parts to the first of Patanjali’s eight limb path, there are also five components to the second limb of niyama. They are sauca (cleanliness), santosa (contentment), tapas (austerities), svadhyaya (self-study), and Isvarapranidhana (devotion). When one is generating a correct extension in an asana, one is also irrigating the body with blood and prana (biological energy). This cleansing of the body, with blood from an even stretch, is sauca. The sense of inner contentment one feels when involved in such a process is, as mentioned above, santosa.

The next three components of niyama involve a deeper level of practice. Tapas, or austerities, can also be defined as a burning desire to give the maximum in a pose, to move beyond self-perceived limitations, in order to cleanse the cells of the body and to prevent impurities from entering. Through regular practice, one learns about the various dimensions of one’s self, from the skin of the body to the core of the being. This is svadhyaya, or self-study. The devotion required to establish a routine of regular practice within everyday life's mundanity can be considered an aspect of Isvarapranidhana. In the case of the asana itself, doing it with the utmost attention and precision in order to achieve correct placement and extension involves a complete involvement, or surrender, into the pose itself.

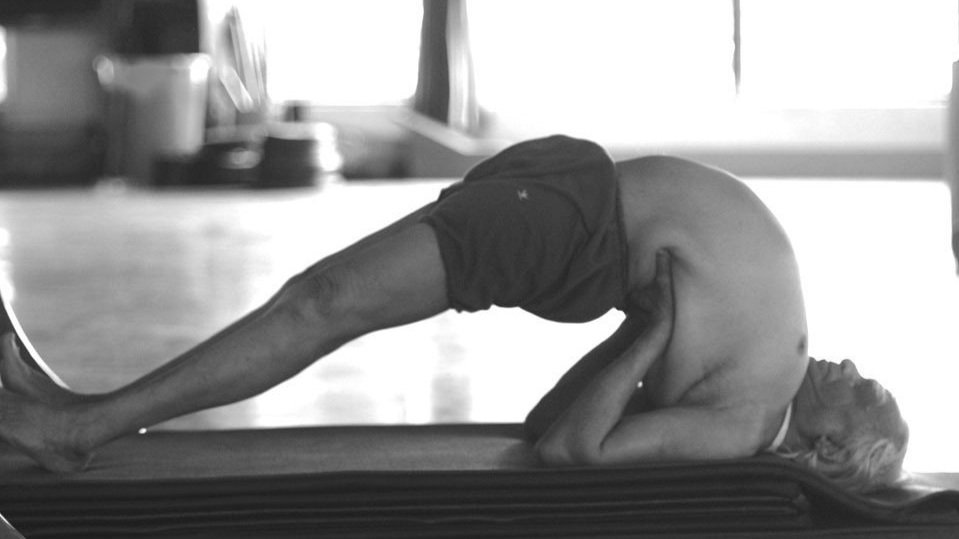

In an interview BKS Iyengar once said: 'The asanas came because I followed the principles of yama and niyama. I involved my entire self—physical, emotional and intellectual. The entire body becomes a basis for meditation. Each pose is meditation. The body is a temple. The ‘atma’ (or soul) needs a clean place to live….. but yama-niyama has to be understood…. it is implicit in my technique.’ Take a look at the following video of Iyengar practising and teaching when he was around 60 years of age to get a better understanding of what he is saying when he describes the yamas and niyamas as the ‘golden keys to unlock the spiritual gates’. here, something that can be difficult to convey with language:

In a similar manner, the principles of yama and niyama are implicit in the way an Iyengar yoga class is conducted. From an outsider's point of view it may seem pedantic to be so thorough with how the feet have to be placed when setting up to go into a pose, or even how a blanket may need to be folded before sitting on it, however it is the cultivation of these principles of yama and niyama that are implicit in this process.

The External Limbs: Asana & Pranayama

It may be surprising that despite there being nearly 200 sutras in the Yoga Sutras, only three are concerned with asana. Patanjali says that asana, or posture, must be steady and comfortable, and that it should involve effortless effort so the mind can be absorbed inwards and not be afflicted by the dualities of opposites. How the steadiness and comfort aspect of asana is incorporated within the practice of Iyengar yoga was mentioned previously. Practitioners are also directed to ‘repose’ within the pose. This is a rethinking and readjusting process so that the body is positioned correctly and its various parts, such as the bones, joints, muscles, fibres and cells, get nourished and soothed. ’This is known as repose in the pose, reflection in action. When the asanas are performed in this way, the body cells, which have their own memories and intelligence, are kept healthy. When the health of the cells is maintained through the precise practice of asanas, the physiological body becomes healthy and mine is brought closer to the soul. This is the effect of the asanas. They should be performed in such a way as to lead the mind from attachment to the body towards the light of the soul so that the practitioner may dwell in the abode of the soul.’

Pranayama, according to Patanjali, is the regulation of the breath in order to remove illusion and make the mind fit for the higher limbs of yoga. In Iyengar yoga pranayama is introduced when one gains a certain amount of proficiency in asana practice, but even within asana itself one learns to synchronise the breath with the movement of the body. In the beginning it is simply inhaling on expansive movements and exhaling on contractive movements, however this is refined as one becomes more proficient. Becoming aware of the tension, expansion and relaxation of the breath within the asana is necessary for deepening the asana towards a meditative action.

The Internal Limbs: Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana & Samadhi

Pratyahara is the fifth limb, and is translated as sense withdrawal. In everyday life our senses are attracted to or repelled by sense objects, to the outside world, and are directed according to our likes and dislikes, our whims and our impulses. They are famously likened to the wild horses of a chariot - the chariot representing ourselves - that are being pulled here and there. Ultimately this is an unsatisfactory way of being. The role of pratyahara is to rein in the senses so that the mind is drawn inwards, is stilled, and is able to work towards the higher, or more subtle, limbs of yoga. In relation to asana Iyengar says ‘when you are thoroughly and totally absorbed in your presentation of the asana, forgetting neither the flesh nor the senses….that is pratyahara.’

Dharana is translated as concentration, and is described by Patanjali as fixing the mind on one place. In asana it is the ability to focus one's attention on one point within the pose. In yoga philosophy the mind does not just exist in the brain, but permeates the entire being. The effort to take one’s attention to the back leg in a wide-legged standing pose, for example, and the ability to create an even extension so that the leg is energetic and straight, is an example of dharana in asana. This is important in cultivating the intelligence of the body, a core aspect of Iyengar yoga, because we all have dull areas of the body that need to be awakened. Props can be useful in this regard, as they help the practitioner to become aware of, and address, these parts.

Dhyana is the penultimate limb, and is also known as meditation. It can be considered as a continuation and deepening of the previous limb of dharana. Whereas in dharana the attention moves between different aspects of the object which is being contemplated, in dhyana the object is perceived in its wholeness. In our asana practice it is the ability to perceive the pose as a single energetic structure, as opposed to separate parts. All the different aspects of the asana are integrated into one single perception of the posture in its wholeness. In this transition the pose is adjusted intuitively, rather than actively using the brain.

Finally there is samadhi, or the state of yoga. BKS Iyengar writes: 'When the attentive flow of consciousness merges with the object of meditation, the consciousness of the meditator, the subject, appears to be dissolved in the object. This union of subject and object becomes samadhi.’ In asana when resistance dissolves and nothing stands between the pose and the one doing it, an inkling of a samadhi state can take place. When the practitioner becomes the pose, as opposed to doing the pose, it becomes samadhi.

No doubt these are lofty goals to work towards within one’s asana practice, however when it is realised that Iyengar yoga is firmly rooted within the context of an ancient philosophical tradition, and that we are attempting to go well beyond the undoubted physical benefits, one can understand why the practice can feel so rich, transformative and profound.

Learn more about the philosophy of Iyengar yoga by attending our monthly Yoga Study Group.

James Hasemer

James Hasemer is the Founder and Director of Central Yoga School and a Senior Iyengar Yoga Teacher, Assessor, and Moderator. He is also currently a Teacher Director on the Iyengar Yoga Australia Board

References

[1] The Tree Of Yoga BKS Iyengar

[2] Light On The Yoga Sutras Of Patanjali BKS Iyengar

[3] Iyengar And The Yoga Tradition Karl Baier (article)

[4] The Yoga Sutras Of Patanjali Edwin Bryant

[5] 70 Glorious Years Of Yogacharya BKS Iyengar Various (Commemorative Volume)

[6] Astadala Yogamala Volume 7 BKS Iyengar (Collected Works)